The Science of Reading

Literacy is a powerful tool for individuals and society

Teaching students to read unlocks their potential for success in school and in life. Children who enjoy reading have better mental wellbeing than their peers who don’t (National Literacy Trust, 2018). Academically, children who are not reading at grade level by the end of third grade struggle in every class, and will continue to fall behind, because over 85 percent of the curriculum is taught through reading (The Children’s Reading Foundation, 2023). And, students who read for pleasure have higher average grades than those who don’t read outside the classroom (Whitten, Labb, Sullivan, 2016).

Each year, millions of US students with limited literacy skills continue to leave high school, either as graduates or dropouts, with limited literacy skills, leaving them unprepared for academic or workplace success in the 21st century economy.

As adults, those individuals are likely to find it more challenging to pursue their goals—whether these involve job advancement, purchasing decisions, being an active citizen, or other aspects of their lives (NCES, 2002). For example, people who have higher levels of literacy are more likely to be employed, work more weeks in a year, and earn higher wages than individuals demonstrating lower proficiencies (NCES, 2002). This means that people with more literacy skills can expect their incomes to increase at least two to three times what they were earning at the beginning of their careers (Lal, 2015).

Literate people also live healthier lives (Lal, 2015). In fact, one study found that 30 minutes of reading lowered blood pressure, heart rate, and feelings of psychological distress just as effectively as yoga and humor (Rizzolo et al., 2009). Literate people are also more likely to participate in civic activities, and are more likely to vote (NCES, 2002).

As many as 50 percent of K-12 students in the United States are struggling with the foundational skills they need to become fluent readers.

Reading deficits disproportionately affect students of color and those from less advantaged backgrounds.

Only 15 percent of Black fourth graders and 28 percent of Hispanic fourth graders showed reading proficiency, compared to 45 percent of white students (NAEP, 2022).

What we know about how people learn to read

The Reading League developed a Defining Guide to provide a common understanding of evidence-based assessments and instructional practices. Most importantly, advances in the science of reading from many fields help educators identify how to effectively assess, teach, and improve students’ reading skills.

What happens in the brain when reading

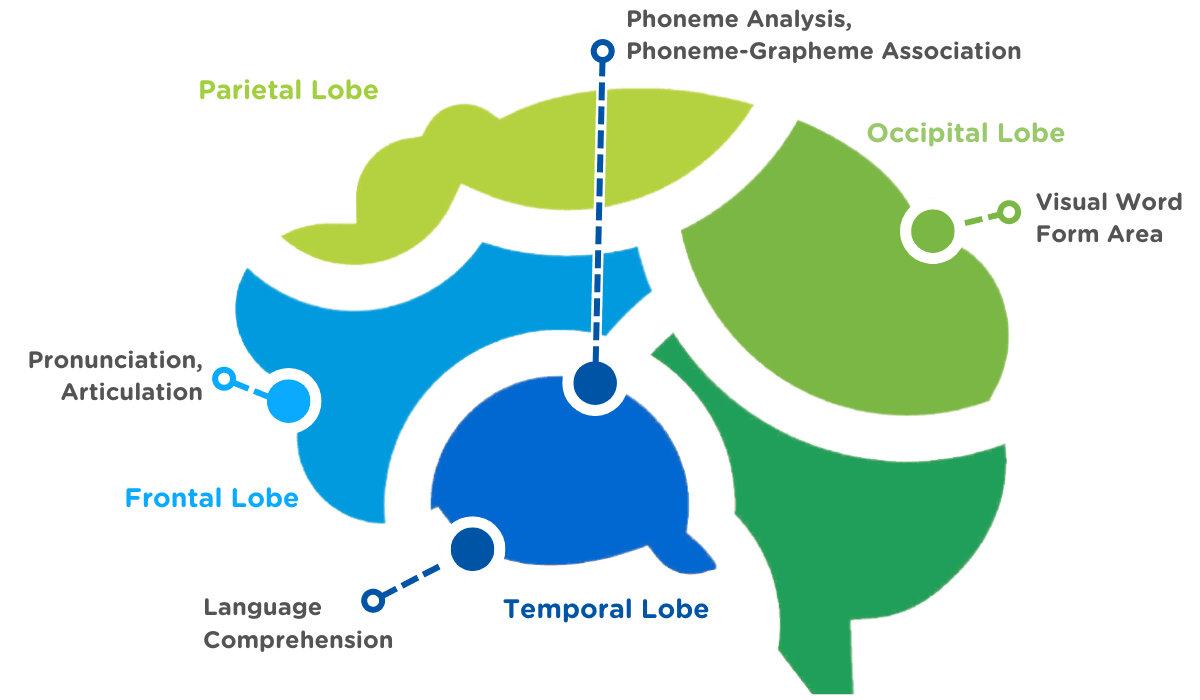

Over the past two decades, research from multiple fields, including neuroscience, communications sciences, cognitive psychology, linguistics, and other sciences have focused on the area of reading development. For example, researchers have identified the areas and networks of the brain that process print, speech sounds, language, and meaning:

- The temporal lobe is responsible for phonological awareness and for decoding and discriminating sounds;

- Broca’s area in the frontal lobe governs speech production and language comprehension; and the angular and supramarginal gyrus link different parts of the brain so that letter shapes can be put together to form words (Edwards, 2016).

The interactions in the brain demonstrate the complexity of acquiring the knowledge, skills, and experiences to become a skilled reader.

The components of skilled reading

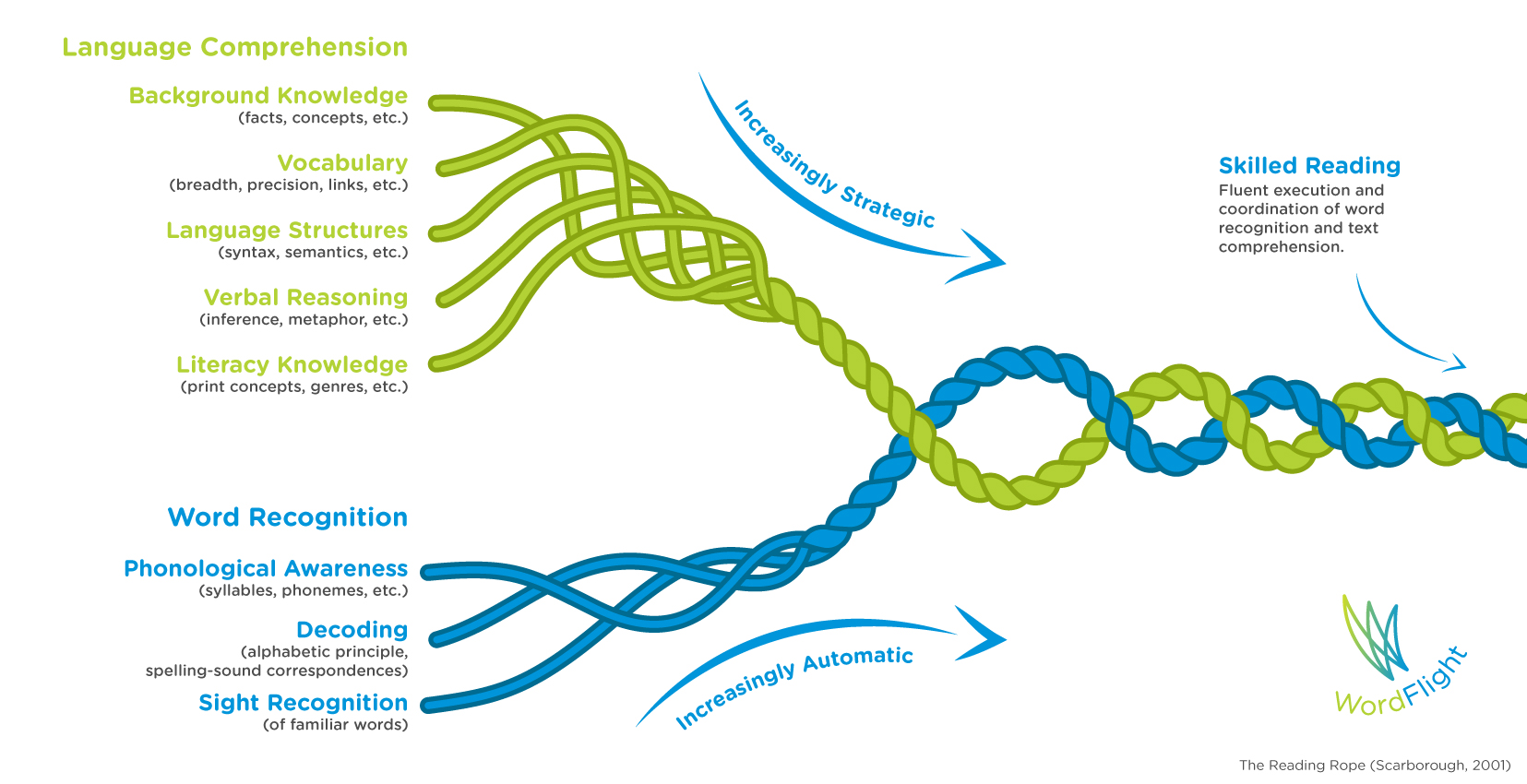

Dr. Hollis Scarborough, a leading reading researcher, studied the relationship between early language development and literacy. She created the Reading Rope as a visual metaphor to demonstrate the interaction of the skills needed to become a proficient reader (2001). Scarborough divided the rope into two main strands:

- Language Comprehension: developing and integrating background knowledge, vocabulary, language structures, verbal reasoning, and literacy knowledge.

- Word Recognition: developing phonological awareness, decoding, and word recognition; which lead to automaticity, accuracy, and fluency when these foundational skills are frequently practiced.

All the components are interconnected and interdependent, and if any strand is weak, it affects the other skills (Staake, 2023). Explicit systematic phonics instruction has been shown to be a necessary component of an effective literacy program to build foundational skills. However, without automatic word recognition, students cannot read with fluency and comprehension.

Strengthening decoding

In the science of reading, decoding means translating the written word into spoken sounds by applying knowledge of sound-letter relationships. For example, if students have challenges with decoding, they may have labored oral reading in which “sounding out” the words is their primary strategy. Decoding is part of Scarborough’s Word Recognition strand.

Research finds that decoding abilities are very predictive of reading comprehension, with decoding accounting for substantially more involvement in comprehension than even spoken language comprehension (Shankweiler et al., 1999). In fact, a randomized control study of students aged 7 to 10 showed that an intervention focusing on decoding skills boosted reading comprehension scores (McCandliss et al., 2003; see Foorman et al., 1998 for similar results).

Many struggling readers, especially those in middle school, receive interventions that focus predominantly on comprehension. Decoding is rarely directly measured, much less targeted for intervention (Apfelbaum, Brown, & Zimmermann, n.d.).

Although an essential skill, decoding isn’t enough to become a fluent reader. While the sound-letter relationships must be learned to support the decoding of words, this knowledge and its use must become automatic in order to develop the expert skills necessary for fluency development.

Focusing on automatic word recognition

Fluent readers go beyond decoding skills to automatically and effortlessly recognize words (Oslund et al., 2018). They can process large quantities of text quickly, with little conscious processing of sound-to-letter mappings. This mental process is known as automatic word recognition and is also part of the Word Recognition strand.

When word recognition skills become automatic, readers can focus on comprehending, or understanding the meaning of the text. That’s when stories come to life. That’s when students can process ever more complex text. And, that’s when students learn to love reading and begin to thrive in school.

Declarative learning is often highly effective for recognizing simple patterns, where explicit relationships are taught. However, more complex patterns are better learned through non-declarative approaches (Ashby & Maddox, 2005). Research findings suggest that the development of automatic word recognition requires both these learning approaches:

- Explicit instruction about how letters link to the sounds of language.

- Practice opportunities to integrate this information into the cognitive processing system to support automaticity and fluency (Apfelbaum, Brown, & Zimmermann, n.d.).

Automatic word recognition is required for fluency and is a critical predictor of fluency development (Roembke et al., 2019). Despite automatic word recognition being an essential prerequisite for students to reach fluency, it is often overlooked in traditional assessment and instruction.

WordFlight targets decoding and automatic word recognition

WordFlight helps students in grades 2-8 build foundational skills and accelerate their learning to become fluent readers. The goal of WordFlight is to help students acquire and use decoding knowledge using targeted practice opportunities, so they learn to automatically deploy this knowledge.

WordFlight is a labor of love from a group of dedicated reading researchers, authors, and cognitive scientists who have relentlessly studied how the science of learning can be integrated into the science of reading to help students learn to read fluently. Meet the team.

As a result, WordFlight uses a proven, learning model based on the science of reading and the science of learning that diagnoses and provides personalized, adaptive instruction to improve important reading skills like decoding, automatic word recognition, and generalization of these skills.

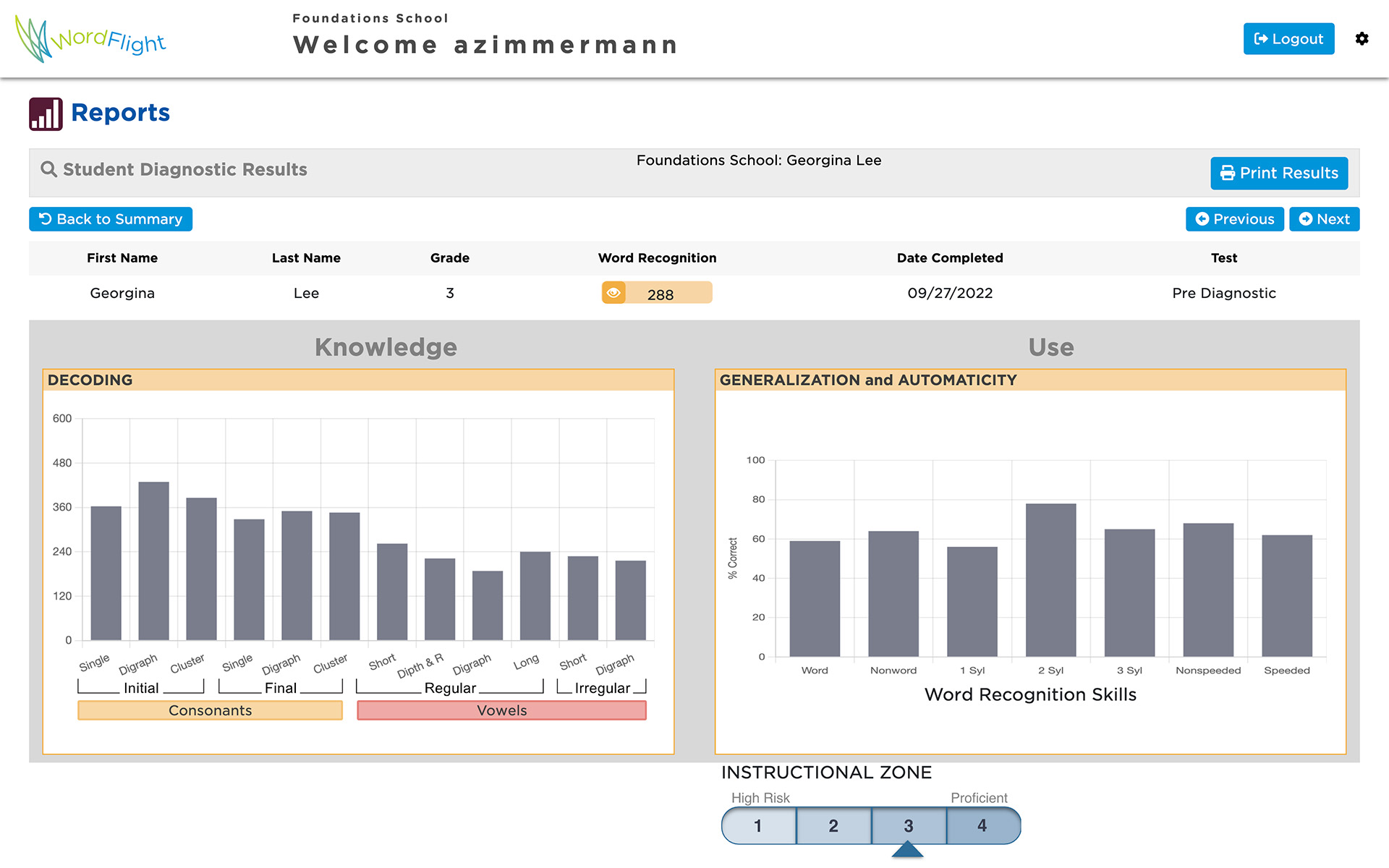

The WordFlight Diagnostic:

- Identifies students’ strengths and gaps in decoding skills with a depth of information not seen in other assessments.

- Measures whether a student can automatically and flexibly use what they know across many contexts to automatically read words.

The WordFlight Instructional Program is the only solution that is designed to build automatic word recognition using the principles of learning science. The tens of thousands of oral and print experiences delivered privately allow diverse learners to repeatedly explore the language and the links between sound and print. This varied and systematic structured practice allows students to gain competence and confidence with the meaning and structure of English through increasingly varied and difficult word experiences.

References

Apfelbaum, K., Brown, C., & Zimmerman, J. (n.d.). Why We Need a New Approach to Reading Assessment and Intervention. Foundations in Learning. https://www.wordflight.com/download/?download=new-approach

Ashby, F. G., & Maddox, W. T. (2005). Human category learning. Annual Review of Psychology, 56(1), 149–178. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev psych.56.091103.070217

Edwards, S. (2016). Reading and the Brain. Harvard Medical School. https://hms.harvard.edu/news-events/publications-archive/brain/reading-brain#:~:text=Among%20them%20are%20the%20temporal,the%20brain%20so%20that%20letter

Foorman, B. R., Francis, D. J., Fletcher, J. M., Schatschneider, C., & Mehta, P. (1998). The role of instruction in learning to read: Preventing reading failure in at-risk children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(1), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.90.2.235

Lal, B. S. (2015). The Economic and Social Cost of Illiteracy: An Overview. International Journal of Advance Research and Innovative Ideas in Education, 1(5), 663-670. http://ijariie.com/AdminUploadPdf/The_Economic_and_Social_Cost_of_Illiteracy__An_Overview_ijariie1493.pdf

McCandliss, B. D., Beck, I. L., Sandak, R., & Perfetti, C. (2003). Focusing attention on decoding for children with poor reading skills: Design and preliminary tests of the Word Building intervention. Scientific Studies of Reading, 7(1), 75–104. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532799XSSR0701_05

National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP). (2022). Explore Results for the 2022 NAEP Reading Assessment. The Nation’s Report Card. https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/reading/?grade=4

National Center for Education Statistics (NCES). (2002). Adult Literacy in America. NCES. http://ijariie.com/AdminUploadPdf/The_Economic_and_Social_Cost_of_Illiteracy__An_Overview_ijariie1493.pdf

National Literacy Trust. (2018, September 26). Mental wellbeing, reading and writing. National Literacy Trust. https://literacytrust.org.uk/research-services/research-reports/mental-wellbeing-reading-and-writing/

Oslund, E. L., Clemens, N. H., Simmons, D. C., & Simmons, L. E. (2018). The direct and indirect effects of word reading and vocabulary on adolescents’ reading comprehension: Comparing struggling and adequate comprehenders. Reading and Writing, 31(2), 355- 379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-017-9788-3

Rizzoo, D., Simpkins, S., Stiskal, D., Zipp, G. P. (2009, January). Stress Management Strategies For Students: The Immediate Effects Of Yoga, Humor, And Reading On Stress. Journal of College Journal of College Teaching and Learning 6(8), 79-88 DOI:10.19030/tlc.v6i8.1117

Roembke, T. C., Hazeltine, E., Reed, D. K., & McMurray, B. (2019). Automaticity of word recognition is a unique predictor of reading fluency in middle-school students. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(2), 314–330. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000279

Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and literacy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and practice. In S. Neuman & D. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook for research in early literacy (pp. 97–110). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Shankweiler, D., Lundquist, E., Katz, L., Stuebing, K. K., Fletcher, J. M., Brady, S., … Shaywitz, B. A. (1999). Comprehension and Decoding: Patterns of Association in Children With Reading Difficulties. Scientific Studies of Reading, 3(1), 69–94. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532799xssr0301_4

Staake, J. (2023, February 6). What Is Scarborough’s Reading Rope and How Do Teachers Use It? We Are Teachers. https://www.weareteachers.com/scarboroughs-rope/

The Children’s Reading Foundation. (2023). What’s the Impact. The Children’s Reading Foundation. https://www.readingfoundation.org/the-impact#:~:text=Academic%2C%20emotional%20and%20social%20issues,dropout%20problems%2C%20and%20juvenile%20crime

The Reading League. (2020). Science of Reading: Defining Guide. The Reading League. https://www.thereadingleague.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Science-of-Reading-eBook-2022.pdf

Whitten, C., Labby, S., & Sullivan, S. L. (2016). The Impact of Pleasure Reading on Academic Success, The Journal of Multidisciplinary Graduate Research, 2(4), 48-64. https://www.shsu.edu/academics/education/journal-of-multidisciplinary-graduate-research/documents/2016/WhittenJournalFinal.pdf